The Story Behind the Greatest Chuck Berry Bootleg You May Never Hear

Thirty-eight years ago, the man who more than anyone else invented rock & roll left it all on a stage in Austin, Texas.

It was April 27, 1986, and Chuck Berry, then 59, was on the final night of a tour that had him headlining a bill of legacy acts that included Chubby Checker, Martha and the Vandellas, the Shirelles and others.

In this era, when Berry was on the road, his typical backing band consisted of “whatever underpaid local rockers the promoter rounded up,” as one biographer put it.

But that night in Austin, Berry was backed by Bo Diddley’s famed bassist Debby Hastings. On drums was St. Louis native Mike Mesey, now 66, who played with Berry everywhere around their shared hometown, from Busch Stadium to Blueberry Hill.

Mesey recalls the Austin crowd being “on fire,” and that instantly galvanized Berry. “It was a perfect storm. He was in the perfect mood. The crowd just set him off right. He looked back at me, smiled and kicked it in,” Mesey says.

Berry opened with “Roll Over Beethoven” and went right into “School Days.”

“It was like a freight train from song one,” Mesey says. By the end of the 14-song set, Berry was ad-libbing lyrics along with his guitar riffs.

“I love you!” he shouted to the crowd during “Johnny B. Goode,” the show’s penultimate number. “You’re all my rock children!”

The real gem of the night was the closer, a version of “Reelin’ and Rockin'” that went on for more than twelve minutes (the studio version runs about three minutes). The horn section from one of the night’s previous acts came up and started jamming. The brass players riffed over Berry’s guitar licks. Audience members got on stage and started dancing.

The technician working the mixing board that night recorded the show. He handed the tape over to the promoter who, about a month later, gave it to Mesey.

“I always say to myself, I think it’s like the greatest rock live version caught on tape of Chuck,” says Mesey.

And now, Mesey is determined to bring that show in Austin to Berry fans across the world — a quest for which he’s spared little effort or expense.

There’s just one problem.

Without the blessing of either Universal Music Group, which owns most of Berry’s recordings, or the Berry estate, it is unclear if Mesey has the right to release the bootleg he’s spent two years toiling over.

COURTESY OF MIKE MESEY

Chuck Berry, left, with Mike Mesey. The two frequently played together during Berry’s St. Louis shows.

Mesey says that between 1986 and 2021, he occasionally retrieved the tape from his home safe to play it for others. Those impromptu audiences were always blown away.

During those decades Mesey enjoyed a robust touring and studio career working with bands such as REO Speedwagon and Head East. Then, at the end of 2021, with COVID causing a lull in Mesey’s schedule, he decided he wanted to do something with the Berry tape.

“I got to thinking, instead of calling somebody and saying, ‘Hey, I want to do this and I want to do that,’ I thought to myself, just get it all completed and get it perfect, then go to everybody and say, ‘It’s finished,'” Mesey says.

It’s a strategy that has yielded an immaculate recording … but one that few people may ever hear.

It took two years and Mesey spending, in his calculation, “six figures” out of his own pocket to bring the bootleg tape’s technical quality up to par with the performance it captures.

The live recording of the show was all captured on one single track on a shoddy cassette. The tempo of the recording started speeding up in places; the keys changed. All that had to be corrected. Working at first in St. Louis and then later at Abbey Road in London, Mesey was able to separate the vocals, guitar, bass and drums into three individual tracks. He then gave the product what he calls a more modern rock mix.

“Rock & roll lovers around the world will just get a blast out of hearing that,” Mesey says.

He has a point. Mesey made several clips of the would-be live album available to the RFT, and his work has clearly paid off. The treble of Berry’s guitar sounds as good as ever and, especially when listening with headphones, the rhythm section is absolutely ripping along behind it. The remixed recording is the embodiment of a whole being greater than the sum of its parts.

“Nobody knows it’s here,” Mesey says. “Nobody knows how good it is.”

Mesey titled the would-be live album Chuck Rocks Live: All My Rock Children and even designed cover art.

But after that, things got tricky, and Mesey needed an engineer of a different sort. He got in touch with Al Watkins, a St. Louis-based attorney with a knack for showing up anywhere that personality, controversy and the legal system collide.

“The thought process here was, ‘How do we get this music out there so it can’t not be heard?'” Watkins says. “Every now and then, the double negative is worthwhile.”

The majority of Berry’s catalog is owned by Universal Music Group, including most of his signature songs he originally recorded in the 1950s for what was then the Chicago-based Chess Records, which form the core of the April 1986 setlist. And that presents some big problems for someone with a bootleg of his music — even if that person himself is playing on the recording.

“He can release anything he wants,” says Michael Nepple, an attorney with Thompson Coburn with expertise in intellectual property law. “The risk is getting nailed on copyright infringement.”

Nepple stresses he isn’t familiar with the specifics of All My Rock Children. But after learning of the project in broad strokes, Nepple says, “The drummer is going to have a lot of problems if this goes out.”

And the damages could be staggering. Speaking generally, Nepple says individuals whose copyright has been infringed upon can sue for multiple types of damages. One type of legal action would be to recoup any money that someone made off another person’s intellectual property, what is called suing for actual damages.

Then there are statutory damages, which, according to Nepple, can run up to $150,000 per infringing work.

“So if Chuck Berry ripped out 15 songs, the guy could be on the hook for either actual damages or $150,000 times 15,” Nepple says.

For the past year, Mesey and Watkins have been working to get the bootleg album released. Watkins says that they approached Universal Music Group about the project and were told, essentially, thanks but no thanks.

One lever might be to get the Berry family on board. How could Universal sue if the Berrys were excited by the project — or even stood to benefit from it?

The exact arrangement, if any exists, between the Berry estate and Universal Music Group is not known. But Nepple says it is not unusual for the estate of legacy artists to have struck a deal with entities like Universal wherein the family can give input on what sort of uses the songs can be put to.

But when it comes to getting the blessing of the Berry family, Watkins says it’s unclear who the decision-maker for the Berry estate is.

“They heard the clips and they loved it,” Mesey says of the family. “They just couldn’t move. I don’t know all the details. But, basically, they just didn’t come back with any kind of [being] able to move forward.”

Gary Pierson, an attorney at Capes Sokol, says he represents Berry’s family and “the entity that controls all rights with respect to his music, likeness and all other intellectual property.” Pierson says the family has declined comment. However, that silence is a response in and of itself.

Berry’s career is replete with his work being pilfered by others. Perhaps most famously, in 1963 the Beach Boys wrote new lyrics to Berry’s song “Sweet Little Sixteen” and had a mega-hit with “Surfin’ U.S.A.” (Berry biographer RJ Smith wrote that Berry likely heard the pilfered smash hit while in prison in Jefferson City. He was later credited as the song’s writer.)

ZACHARY LINHARES

Paul Berry III is Chuck Berry’s great-nephew — and a candidate for lieutenant governor of Missouri.

As for others making money off his music, “He didn’t tolerate that at all,” says Wayne Schoeneberg, Berry’s longtime attorney in St. Charles (Schoeneberg is not involved with the estate). “He was very protective of his own intellectual property.”

For 20 years, Schoeneberg helped Berry handle issues related to the rights and the licensing of his music. Schoeneberg says Berry had a good business sense, though at times he would turn down deals, even lucrative ones, if they didn’t feel right.

“He was just a unique individual and had his own way of addressing everything,” Schoeneberg says. “He and I would frequently disagree on approaches, but he was the boss.”

Paul Berry III is the rock & roll star’s great-nephew and also happens to be running for lieutenant governor. He makes clear that he does not represent the Berry estate, but, speaking directly to this issue, says he is alarmed — in more ways than one — by the idea that someone would spend at least $100,000 of their own money and travel to London to work on a record without getting approval from either of the two entities that own the underlying music.

“From what is being explained, I would really be concerned about whether he may have mental health issues,” Berry III says. “I would definitely want to pray for his health in that regard.”

He adds, “It’s a shame the godfather of rock & roll can’t rest in peace without people pillaging his grave.”

ZACHARY LINHARES

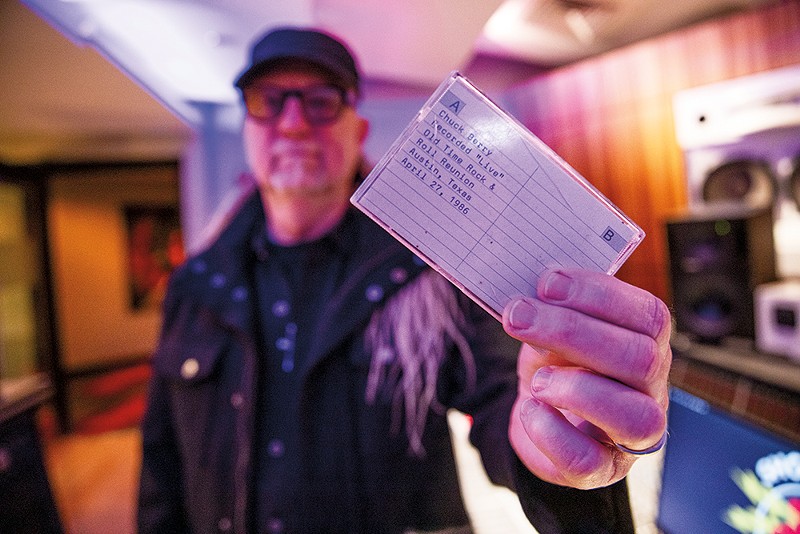

Mike Mesey, left, and Sam Maul at Shock City Studios in St. Louis. The two worked for months pulling out and cleaning up the Berry tape.

Mesey is hardly the first creative person, musician or otherwise, to spend two years and $100,000 on a project that is hardly a sure thing — only to be called crazy.

And for the record, he says the effort wasn’t always as quixotic as it appears now. He doesn’t want to go into details, but says that for a while he and attorney Watkins were working with an intermediary to the Berry family, until, for reasons that remain opaque, things “hit a wall.”

Mesey is taking it all in stride. Despite the album not even being out in the world, he still says it’s one of the most special things he’s ever done.

The reason he’s talking to the RFT and sharing clips of the work is that he’s hoping that once people get a taste of it, they’ll clamor for more. And if that happens, maybe Berry fans from around the world can will the album into existence.

“I didn’t go into this to do anything else other than to honor Chuck Berry,” he says. “The world needs to hear this. This is a tape like no other ever recorded.”

Subscribe to Riverfront Times newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

Comments are closed.